Fast food. Grab and go. On the run. Slogans slapped on menus, food packets and billboards, part cause and part symptom of our cultural shift towards eating quickly, mindlessly, and in transit. When we do sit down to eat, it’s often alone, in front of a screen. Even with company, many of us can confess to phones on table, timekeeping before the next appointment. Here’s a check in question - thinking back to your last meal, do you remember what your food tasted like? Texture? Aroma? If you’re finding the recall a little sketchy, join the club. Most likely, your mind wasn’t on the food at all.

Old trick, new audience

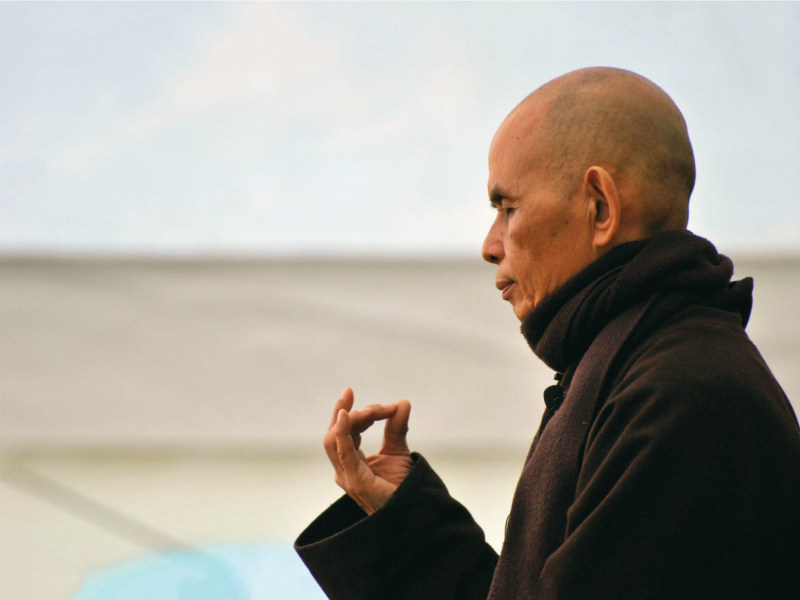

Mindful eating is an age-old practice currently gaining traction in the pop-culture sphere, a sort of peaceful protest against our disconnected relationship with food and eating. Of all the proponents of mindful eating, Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh is the most prominent. Founder of the monastic community Plum Village (Bordeaux, France) and co-author of Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life, Hanh has amassed a massive audience world wide, helped in large part by Oprah’s endorsement. Hanh believes eating absent-mindedly is the root cause of many health problems, including obesity, and that mindful eating is an essential ingredient to living a conscious, productive life. Though Hanh's message has universal application, it has particularly resonated in affluent Western societies, where we suffer not from lack but from oversupply, and from interminable busyness.

Thich Naht Hanh, Buddhist master renowned for mindfulness teachings.

Mindfulness goes mainstream

To understand mindful eating, we must first unpack the concept of mindfulness and its place in Western culture. Buddhist philosophies have kept Zen masters in good health for centuries, but the practice of mindfulness wasn’t embraced by Western health practitioners until the mid 20th Century. As psychologists and academics cottoned on to the evidence-based argument for mindfulness and meditation in managing pain and mental health, they began integrating Buddhist philosophies and practices into their approach. One such professor is Jon Kabat-Zinn, who developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MSBR) in the 1970s to treat patients with chronic pain (MBSR is still offered in many hospitals and medical institutions today). Kabat-Zinn is now considered one of the pre-eminent voices in the field of mindfulness as it pertains to the medical profession, successfully integrating Buddhist and yogic teachings with scientific findings. In his book Wherever You Go There You Are, Kabatt-Zinn defines mindfulness as, “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” In other words, mindfulness means to become aware of the here and now.

Science says

Sounds easy enough, but resisting distraction may prove more difficult than it looks on paper. It’s worth it, though, if scientific evidence is anything to go by. Countless studies attest to the myriad benefits of practicing mindfulness, including stress reduction, some balancing out of mental disorder symptoms, and improved sleep, mood, memory and focus. One typical study conducted on a group of 20 novice meditators showed that after a 10 day retreat, subjects reported less rumination and depressive symptoms compared to the control group. They also had a better working memory capacity, and were able to sustain better attention.

Build your brain

Far beyond feel-good vibes, mindfulness practice can actually change the structure of your brain. A 2011 study took MRI images of sixteen “meditation-naive participants” before and after they underwent an eight-week mindfulness program. Participants showed an increase of grey matter in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a part of the brain located deep inside the forehead associated with self-regulation, and the way we direct attention and behavior. There was also an increase in the amount of grey matter in the hippocampus, part of the brain’s limbic system, responsible for the regulation of emotions and mental functioning. Research like this adds a whole new aspect to the discussion of emotional and binge eating in particular, suggesting that mindfulness may in fact increase your cognitive ability to regulate emotions without needing to use food.

Create space for mindfulness practice at meal times. No screens, just you and your food.

The gut-body connection

Of all the benefits of mindful eating, reconnecting our minds with our bodies is especially relevant to those of us who were told as children that we couldn't leave the table until we'd finished our dinner. A rather humorous US study on visual cues and eating used self-refilling soup bowls to measure how much people would eat if their bowls never emptied. Unsurprisingly, those people eating soup from literally bottomless bowls consumed a whopping 73% more soup than those eating from regular bowls, although they did not believe they had consumed more, and they didn’t report feeling more sated than those who ate from normal bowls. Point being, we tend to eat and even experience satiety with our eyes. In practicing mindfulness during meals, we’re more likely to tune into how our body is actually experiencing the meal and whether we’ve had enough, regardless of whether the plate is clean or not.

We may also find we can better discern between emotional hunger and physical hunger, becoming increasingly aware of when we’re eating out of boredom, or when we’re choosing certain foods for comfort rather than nourishment. We begin to actually enjoy eating, rather than relating to it as a chore or a quick fix. Eating in this way is obviously far better for our physical health, but also has positive implications for self esteem, stress management, mental health, and our overall enjoyment of day to day life.

Monkey see, monkey do

To eat mindfully is simply to engage with a sense of awareness around food, slowing down and being present during the experience. Mindful.org defines mindful eating as:

· Listening to your body (eating when hungry, stopping when full)

· Eating at regular times

· Eating at set places (not in car, while watching TV, etc.)

· Eating with others

· Eating foods that a nutritionally healthy

· When you eat, just eat (no multi-tasking)

· Acknowledging your food – who made it? Where are the ingredients from? How did it get to your plate?

Hanh also suggests practicing gratitude at meal times, perhaps your own version of the traditional prayer of grace before or after the meal.

Do try this at home

Jon Kabat-Zinn developed this Raisin Meditation to give his stress-reduction students a sensory experience of being mindful. You can use this exercise as a taster (see what we did there?!) of mindful eating meditation.

1. Grab a raisin, or any small piece of dried fruit. Hold it in your hand. Pretend you’ve never seen it before. Be curious.

2. Take time to really see the raisin. What colour is it? Are there different shades? Is it smooth or wrinkly?

3. Touch the raisin, and feel what it feels like. Maybe close your eyes to get a better sense of touch.

4. Hold the raisin to your nose. What does it smell like? Does the scent make you feel like eating it?

5. Place the raisin in your mouth. What does it feel like on your tongue?

6. When you’re ready, consciously chew the raisin. Don’t swallow yet. Notice the taste of the raisin and the texture changing while you chew.

7. Pause before you swallow the raisin. What does it feel like just before you decide to swallow it? When you do swallow, what does it feel like going down your throat?

Mindful eating exercise: contemplate the raisin.

And just like that, you’ve been meditating. For a guided version of the Raisin Meditation check out this video. To integrate mindfulness into your daily routine, check out this list of recommended apps on the Plum Village website.